FBI Investigations and DOJ Prosecutions: Fighting for Your Privacy Rights

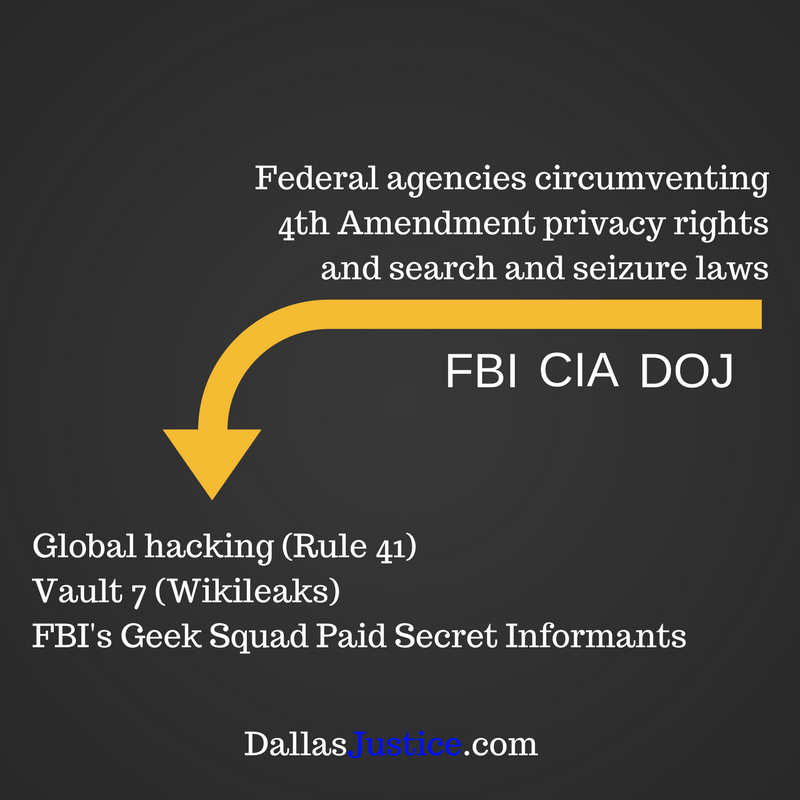

Of paramount concern to criminal defense attorneys is protecting due process and making sure that any investigation and prosecution by the government abides by constitutional protections like limited police powers, the right to privacy, and search and seizure protocols.

Criminal Defense and Privacy Protections

This is true for the underlying investigation into criminal activity. It is also vital for communications between the criminal defense lawyer and his client. See, Privacy of Lawyer-Client Communications In Danger: The Growing Need For Greater Protections Of Communications Between Attorney And Client.

Today, more and more, the fight to defend clients against government intrusion is getting bigger.

Consider what is happening right now regarding federal investigatory powers and the actions of federal agencies tasked with assisting federal prosecutors in building their case. Here are three examples.

________________________________

1. Amended Rule 41 Gives Global Hacking Power to Feds

Last fall, we discussed the expansion of federal investigative powers through an amendment to the federal procedural rules. See, “FBI’s New Global Hacking Rule: Amended Federal Rule 41 Danger To Your Privacy.”

It gives lots of power to the FBI – and it became law even though lawmakers from both sides of the aisle and both houses of Congress were worried about it. Read the letter sent to then Attorney General Loretta Lynch signed by Mike Lee and Al Franken, among others, in the post. It’s been nicknamed the “Rule 41 Letter.”

The amendment to Federal Rule 41 allows the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) to obtain search warrants for computers that are located anywhere in the world. Federal judges are given the power to approve federal investigations into computer databases located on foreign soil.

Read the changes made to Rule 41 of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure here. It’s already been okayed by SCOTUS, by the way.

2. WikiLeaks’ Vault 7 and Federal Government Cyber Hacking

This week, a new WikiLeaks release is circulating under the name “Vault 7.” You can read the WikiLeaks news release online here.

According to WikiLeaks, this is the “largest ever publication of confidential documents” on the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). It’s the first of a series.

This first dump is called “Year Zero.” It discusses things like CIA malware being placed on smartphones and uploaded into popular software like Microsoft Windows as well as into the operating systems of smart TVs.

It allows for access to the private data and information. It also allows for remote control of the device by the federal agency.

This apparently has been done secretly, without warrants, and it’s not clear how many citizens’ phones, computers, or televisions are involved. Or how the information has been used against them. (This is a developing story at the time of this post.)

3. Paid FBI Informants Working at Geek Squad

Last month, Techdirt reported on the FBI paying people to inform on customers at their job. They are confidential informants who are tasked with informing the federal government if they spot any suspicious cash transactions in the course of their work. Are they working at a bank? Nope.

According to Techdirt and its sources, these FBI informants are working at Geek Squad over there at the local Best Buy store. Techdirt’s court records disclose that the Geek Squad employees got paid $500 to snoop into customer computer files.

The federal government was then using stuff obtained by these informants in federal prosecutions. How could they justify this? They argue it is a “private search” which is acceptable in criminal investigations.

What is not acceptable in a federal criminal investigation is approval of illegal searches that avoid constitutional search warrant requirements.

The “Private Search” Problem: Was the Geek a Government Agent?

Here’s the thing. When a private citizen snoops around on a computer hard drive, then they aren’t required to get a search warrant under the Fourth Amendment. They are not the government, and this is called a “private search.”

SCOTUS has held their search may be wrong and it may violate privacy laws, but it does not violate the Fourth Amendment protections regarding search warrants. See, e.g., United States v. Jacobsen, 466 U.S. 109, 115 (1984).

That changes if that private person is really a government agent. There is precedent that explains how someone crosses the line from private nosy parker to FBI worker bee. And if they meet the requirements, then the Fourth Amendment protections do apply to their actions. The stuff that was discovered can be excluded and barred from being used against the defendant.

To learn more, read “Fourth Amendment Applicability: Private Searches “by Priscilla Grantham Adams, published by the National Center for Justice and Rule of Law in 2008.

Federal Law Governing Actions of Federal Law Enforcement

So, where are the laws here? There are federal statutes that were passed by Congress to implement the Fourth Amendment’s protections and control the police power of federal law enforcement.

For instance, laws have been on the books governing the use of electronic surveillance by federal agencies since the 1960s. Electronic surveillance protocols are found in Title III of the United States Code, specifically 18 U.S.C. § 2510, et seq.

These laws apply to the federal government’s use of things like wiretaps and other forms of electronic surveillance. Under federal law, there are penalties (both criminal and civil) for government agents that illegally use electronic surveillance or unlawfully disclose evidence discovered. See ,18 U.S.C. §§ 2511; 2515; 2518(10); 2520.

For more information, check out the United States Attorney General’s Criminal Resource Manual at 31.

Fourth Amendment Protection and Right to Privacy

The Fourth Amendment of the United States Constitution provides that all citizens are to be protected and kept free from unreasonable searches and seizures by the government. You and I have a right to privacy.

It’s not unlimited. You and I have a right to privacy when there is a reasonable expectation of privacy over the documents or information. What’s that? SCOTUS provides this test in Katz v. United States:

- the person must hold an actual, subjective expectation of privacy; and

- society must be prepared to recognize that expectation as objectively reasonable.

In a criminal investigation, what happens? The police must get a search warrant before they can snoop if there is a reasonable expectation of privacy involved. Law enforcement must appear before a judge and prove up facts that establish probable cause to override the privacy rights of the individual because of a concern that a crime has been or is being committed.

Or at least that is the law on the books. Thing is, from a criminal defense perspective, the reality is that more and more often defense lawyers must be prepared to defend their clients in motions to exclude and motions to suppress after the fact.

This is because unlawful searches are apparently happening right now. Your protection? Defense lawyers must fight in court to block things obtained in illegal and unlawful searches from being entered into evidence.

Defense attorneys are the legal protections against illegal government intrusions. Not prosecutors. Not internal government policies. That’s today’s reality.

___________________________________

For more information, check out our web resources and Michael Lowe’s Case Results

and read his in-depth article, “TOP 10 DEFENSE MISTAKES IN FEDERAL CONSPIRACY CASES AND HOW TO AVOID THEM.”

Comments are welcomed here and I will respond to you -- but please, no requests for personal legal advice here and nothing that's promoting your business or product. Comments are moderated and these will not be published.

Leave a Reply